Here's me at the gate to St. John's Catholic Cemetery in the Portland neighborhood, where

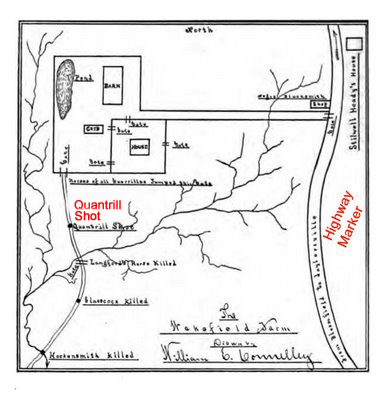

Quantrill was buried after he died June 6, 1865, in a Louisville hospital. At the time, the cemetery was known as St. Mary's. After being shot in the back, the guerrilla lingered for nearly a month, paralyzed from the chest down, before succumbing to his wounds.

Quantrill had converted to Catholicism shortly before his death. According to the burial register provided by the Archdiocese of Louisville,

Quantrill was buried here on June 7 -- along with four children whose first names are unrecorded. The grave is just inside the gate, to the left, in an unmarked grave in lot 624. This gate faces Duncan Street, but at the time of

Quantrill's death, this was the location of the caretaker's house and the main entrance was off 26

th Street, to the north. A newspaper editor and former childhood friend of

Quantrill's from Canal Dover, Ohio, by the name of William Walter Scott had his bones (illegally) dug up in 1887. Scott sold some of the bones to the Kansas State Historical Society. The skull was later used in fraternity

initiation rituals -- nicknamed "Jake" and with red Christmas lights glowing in the

eyesockets. The skull was finally reburied on Oct. 30 (my birthday) in 1992 in the Fourth Street Cemetery at Dover. The bones from the Kansas historical society were buried a few days earlier at the Confederate Cemetery at

Higginsville, Missouri, with military honors. That devil

Quantrill is finally at rest. Expect

I, Quantrill sometime in 2008, as I've just delivered the manuscript and the production process takes six months to a year. I haven't seen the cover art yet, but I'll post it when I get it.

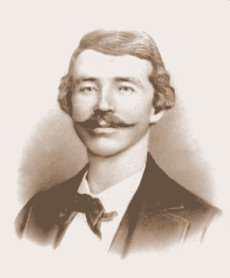

William Clarke Quantrill was born 170 years ago today at Canal Dover, Ohio.

William Clarke Quantrill was born 170 years ago today at Canal Dover, Ohio.