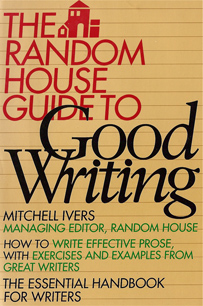

A fine book is Mitchell Ivers's The Random House Guide to Good Writing. Ivers was managing editor of RH when the book was published in 1991, but he's now senior editor at Pocket Books. His book is just one of a very few writing how-tos I've found helpful, and my copy was given to me years ago by my friend and fellow author Fred Bean -- now the late Fred Bean. And speaking of Fred, his funeral was so strange and poignant (outdoors, with doves and mysterious women weeping in back) that it must eventually become a scene in one of my novels. But back to this book by Ivers, which has been on my writing desk for the last few weeks, along with The Elements of Style and The American Heritage Dictionary. I'm in the midst of proofing galleys of I, Quantrill, to be released in May 2008 by New American Library, and I find the Ivers book an excellent reference. In the interest of disclosure, NAL is an imprint of Penguin, but I don't deal with Ivers because he is so far up the food chain. The Guide is still in print and can be had in a mass market edition for about seven bucks from Amazon.

A fine book is Mitchell Ivers's The Random House Guide to Good Writing. Ivers was managing editor of RH when the book was published in 1991, but he's now senior editor at Pocket Books. His book is just one of a very few writing how-tos I've found helpful, and my copy was given to me years ago by my friend and fellow author Fred Bean -- now the late Fred Bean. And speaking of Fred, his funeral was so strange and poignant (outdoors, with doves and mysterious women weeping in back) that it must eventually become a scene in one of my novels. But back to this book by Ivers, which has been on my writing desk for the last few weeks, along with The Elements of Style and The American Heritage Dictionary. I'm in the midst of proofing galleys of I, Quantrill, to be released in May 2008 by New American Library, and I find the Ivers book an excellent reference. In the interest of disclosure, NAL is an imprint of Penguin, but I don't deal with Ivers because he is so far up the food chain. The Guide is still in print and can be had in a mass market edition for about seven bucks from Amazon.

Thursday, December 27, 2007

Ivers on Writing

A fine book is Mitchell Ivers's The Random House Guide to Good Writing. Ivers was managing editor of RH when the book was published in 1991, but he's now senior editor at Pocket Books. His book is just one of a very few writing how-tos I've found helpful, and my copy was given to me years ago by my friend and fellow author Fred Bean -- now the late Fred Bean. And speaking of Fred, his funeral was so strange and poignant (outdoors, with doves and mysterious women weeping in back) that it must eventually become a scene in one of my novels. But back to this book by Ivers, which has been on my writing desk for the last few weeks, along with The Elements of Style and The American Heritage Dictionary. I'm in the midst of proofing galleys of I, Quantrill, to be released in May 2008 by New American Library, and I find the Ivers book an excellent reference. In the interest of disclosure, NAL is an imprint of Penguin, but I don't deal with Ivers because he is so far up the food chain. The Guide is still in print and can be had in a mass market edition for about seven bucks from Amazon.

A fine book is Mitchell Ivers's The Random House Guide to Good Writing. Ivers was managing editor of RH when the book was published in 1991, but he's now senior editor at Pocket Books. His book is just one of a very few writing how-tos I've found helpful, and my copy was given to me years ago by my friend and fellow author Fred Bean -- now the late Fred Bean. And speaking of Fred, his funeral was so strange and poignant (outdoors, with doves and mysterious women weeping in back) that it must eventually become a scene in one of my novels. But back to this book by Ivers, which has been on my writing desk for the last few weeks, along with The Elements of Style and The American Heritage Dictionary. I'm in the midst of proofing galleys of I, Quantrill, to be released in May 2008 by New American Library, and I find the Ivers book an excellent reference. In the interest of disclosure, NAL is an imprint of Penguin, but I don't deal with Ivers because he is so far up the food chain. The Guide is still in print and can be had in a mass market edition for about seven bucks from Amazon.

Tuesday, December 25, 2007

A fine pair from Texas

Two winners from the Texas Monthly 2008 Bum Steer Awards, one about a former Pittsburg State University football coach and another about a television journalist who was nabbed for suspicious behavior in the maternity wards of a couple of Amarillo hospitals.

"Of all the Bum Steer sagas that played out over the past year, however, none was stranger than that of the man ESPN called “dumber than a blocking sled.” Yep, it’s the Aggies’ own Dennis Franchione. His $2 million salary evidently wasn’t enough; he moonlighted as the author of a VIP newsletter, which he sent out by e-mail to 23 well-heeled boosters willing to pay $1,200 for inside dope about injuries and recruits. Unsportsmanlike conduct! When A&M learned of his other gig, the university had to report two rules violations to the NCAA. Even beating Texas two years in a row couldn’t keep him in his job. Congrats, Coach Fran. You’re the Bum Steer of the Year."

Well, my (admittedly slight) connection to Franchione is that I got my undergraduate degree at PSU. I often say in my journalism class that sports really isn't news unless they execute the losers. But I'll make an exception for greed and corruption.

And this gem:

"Coming up at ten: She does five. Cecelia Lynn Coy-Jones, a reporter for KCBD-TV, in Lubbock, was arrested for attempted aggravated kidnapping after lurking in the maternity wards of two Amarillo hospitals, because, she claimed, she was investigating how secure they were from would-be kidnappers."

I'm all for enterprise reporting, but when you appear to be a threat to children, you're begging for trouble. My advice to Coy-Jones: While the occassional stolen baby story makes for breathless copy, it's the damned politicians and bearucrats that really need watching. Lurk in city hall instead.

"Of all the Bum Steer sagas that played out over the past year, however, none was stranger than that of the man ESPN called “dumber than a blocking sled.” Yep, it’s the Aggies’ own Dennis Franchione. His $2 million salary evidently wasn’t enough; he moonlighted as the author of a VIP newsletter, which he sent out by e-mail to 23 well-heeled boosters willing to pay $1,200 for inside dope about injuries and recruits. Unsportsmanlike conduct! When A&M learned of his other gig, the university had to report two rules violations to the NCAA. Even beating Texas two years in a row couldn’t keep him in his job. Congrats, Coach Fran. You’re the Bum Steer of the Year."

Well, my (admittedly slight) connection to Franchione is that I got my undergraduate degree at PSU. I often say in my journalism class that sports really isn't news unless they execute the losers. But I'll make an exception for greed and corruption.

And this gem:

"Coming up at ten: She does five. Cecelia Lynn Coy-Jones, a reporter for KCBD-TV, in Lubbock, was arrested for attempted aggravated kidnapping after lurking in the maternity wards of two Amarillo hospitals, because, she claimed, she was investigating how secure they were from would-be kidnappers."

I'm all for enterprise reporting, but when you appear to be a threat to children, you're begging for trouble. My advice to Coy-Jones: While the occassional stolen baby story makes for breathless copy, it's the damned politicians and bearucrats that really need watching. Lurk in city hall instead.

That's no moon... it's season's greetings.

Wednesday, December 19, 2007

If Bush thinks it's bad... it must be good.

In my journalism classes, I stress the importance of open records and require all of my students to file at least one request per semester. Secrecy, however, has been the rule at the Bush White House, and a campaign has been waged to diminish FOIA -- the federal open records act -- and to encourage officials to ignore, delay, and deny requests. The issue is so important that I include here, in full, an upate on an attempt to strengthen FOIA.

From the National Security Archive:

House Poised to Pass FOIA Reform Bill

Bill Provides “Common Sense” Solutions for Openness Problems:

Penalties for Delays, Tracking Systems for Requests,

Ombuds-style Office to Mediate Disputes, Better Agency Reporting

Reforms Recommended by Archive Audits and Testimony

Washington, DC, December 18, 2007 – The House of Representatives will vote today on a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) reform bill (S. 2488) that passed the Senate by unanimous consent on December 14. The bill aims to fix some of the most persistent problems in the FOIA system, including excessive delay, lack of responsiveness, and litigation gamesmanship by federal agencies. If passed by the House today, it will be sent to the President’s desk for approval.

“Our six government-wide audits of FOIA performance show that these bipartisan changes to the Freedom of Information Act are common sense solutions,” remarked Meredith Fuchs, general counsel of the National Security Archive. “This bill establishes tracking systems for FOIA requests like FedEx uses for packages, actually penalizes agencies for the first time for delays that our audits found could reach 20 years, and sets up an office to mediate disputes as an alternative to litigation.”

The bill in front of the House today represents a bipartisan effort that has stretched over several years, spearheaded by Senators Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and John Cornyn (R-TX), the original co-sponsors of the OPEN Government Act of 2007, Senator Jon Kyl (R-AZ), and Congressman Henry Waxman (D-CA). Efforts to amend the FOIA have faced stumbling blocks in part because of strong administration opposition to passage of earlier versions of this FOIA reform bill in both the House and the Senate.

“This is the bill that President Bush wrote an executive order to try to prevent,” said Tom Blanton, director of the Archive, referring to E.O. 13392 (December 14, 2005), which called for a “citizen-centered and results-oriented approach” to FOIA, established Chief FOIA Officers at each of 92 major agencies, and required agencies to evaluate their FOIA programs and draft improvement plans.

The new law would mandate tracking numbers for FOIA requests that take longer than 10 days to process to ensure they will no longer fall through the cracks, require agencies to report more accurately to Congress and the public on their FOIA programs, create a new ombuds office at the National Archives to mediate conflicts between agencies and requesters, clarify the purpose of FOIA to encourage dissemination of government information, and provide incentives to agencies to avoid litigation and processing delays.

“Congress is acting to improve the FOIA for the first time in more than a decade, since the electronic FOIA amendments of 1996, but Congressional and public oversight will be essential for the law’s success,” Blanton noted. “Our Knight Open Government Survey in 2007 found that only one in five federal agencies fully complied with the 1996 law, even after 10 years of implementation.”

From the National Security Archive:

House Poised to Pass FOIA Reform Bill

Bill Provides “Common Sense” Solutions for Openness Problems:

Penalties for Delays, Tracking Systems for Requests,

Ombuds-style Office to Mediate Disputes, Better Agency Reporting

Reforms Recommended by Archive Audits and Testimony

Washington, DC, December 18, 2007 – The House of Representatives will vote today on a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) reform bill (S. 2488) that passed the Senate by unanimous consent on December 14. The bill aims to fix some of the most persistent problems in the FOIA system, including excessive delay, lack of responsiveness, and litigation gamesmanship by federal agencies. If passed by the House today, it will be sent to the President’s desk for approval.

“Our six government-wide audits of FOIA performance show that these bipartisan changes to the Freedom of Information Act are common sense solutions,” remarked Meredith Fuchs, general counsel of the National Security Archive. “This bill establishes tracking systems for FOIA requests like FedEx uses for packages, actually penalizes agencies for the first time for delays that our audits found could reach 20 years, and sets up an office to mediate disputes as an alternative to litigation.”

The bill in front of the House today represents a bipartisan effort that has stretched over several years, spearheaded by Senators Patrick Leahy (D-VT) and John Cornyn (R-TX), the original co-sponsors of the OPEN Government Act of 2007, Senator Jon Kyl (R-AZ), and Congressman Henry Waxman (D-CA). Efforts to amend the FOIA have faced stumbling blocks in part because of strong administration opposition to passage of earlier versions of this FOIA reform bill in both the House and the Senate.

“This is the bill that President Bush wrote an executive order to try to prevent,” said Tom Blanton, director of the Archive, referring to E.O. 13392 (December 14, 2005), which called for a “citizen-centered and results-oriented approach” to FOIA, established Chief FOIA Officers at each of 92 major agencies, and required agencies to evaluate their FOIA programs and draft improvement plans.

The new law would mandate tracking numbers for FOIA requests that take longer than 10 days to process to ensure they will no longer fall through the cracks, require agencies to report more accurately to Congress and the public on their FOIA programs, create a new ombuds office at the National Archives to mediate conflicts between agencies and requesters, clarify the purpose of FOIA to encourage dissemination of government information, and provide incentives to agencies to avoid litigation and processing delays.

“Congress is acting to improve the FOIA for the first time in more than a decade, since the electronic FOIA amendments of 1996, but Congressional and public oversight will be essential for the law’s success,” Blanton noted. “Our Knight Open Government Survey in 2007 found that only one in five federal agencies fully complied with the 1996 law, even after 10 years of implementation.”

Monday, November 12, 2007

Unnatural Bridge

Ozark Olympus

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

Times Square

Sunday, September 30, 2007

The Beacon

Tuesday, September 18, 2007

Amazing Grace 2001

Back in 2001, I attended the Missouri Shape Note Convention. The following story and photos were first published in The Joplin Globe. My friend, Bill Caldwell, introduced me to the fascinating culture of Shape Note singing. The following story was picked up the by the AP, can still be found elsewhere on the Web, and it remains one of my favorite story-and-photos packages. Cassie Franklin, the singer in the photo below, was later featured on the soundtrack of the movie Cold Mountain.

PINCKNEY, Mo.--A stone's throw north of the Missouri River, where Highway 94 crosses a one-lane bridge and wends its way across the rich bottom land toward Jefferson City, shines a white country church against the muted background of late winter.

PINCKNEY, Mo.--A stone's throw north of the Missouri River, where Highway 94 crosses a one-lane bridge and wends its way across the rich bottom land toward Jefferson City, shines a white country church against the muted background of late winter.

Here, beneath the peaked roof of the 131-year-old St. John's United Church of Christ, time stood still for an eclectic group of singers who practice an archaic form of music known as Sacred Harp.

"It expresses your feelings about God, about how it feels deep down inside your heart,"explained 48-year-old Alice Moran, who was one of a handful of Joplin-area singers at the two-day convention.

Others, however, said religion isn't necessary.

Gary Gronau, a 57-year-old folk music fan and self-described '60's civil-rights activist from St. Louis, cited the music itself as the biggest draw.

"In this room there are a lot of people who are very strongly religious, and then there are people who are atheists--like me," he said.

Unlike most forms of music, which are intended for an audience, Sacred Harp is meant to be experienced. Harpers sing primarily for the joy of singing, said Gronau, and he repeated a quote attributed to legendary Georgia singer Hugh McGraw: "I will travel across the country to sing Sacred Harp, but I wouldn't walk across the street to listen to it."

Unlike most forms of music, which are intended for an audience, Sacred Harp is meant to be experienced. Harpers sing primarily for the joy of singing, said Gronau, and he repeated a quote attributed to legendary Georgia singer Hugh McGraw: "I will travel across the country to sing Sacred Harp, but I wouldn't walk across the street to listen to it."

Hollow square

For the uninitiated, the sound can be unpleasant. The lyrics are difficult to understand, unless a printed version is handy, and the seating arrangement of the singers is unlike that of any other kind of performance; unless you're participating, you're looking at their backs.

Members of the congregation sit in what is traditionally called a "hollow square," facing one another, and the music is divided into four parts, from bass to treble, with the melody carried by the tenors.

Song leaders stand in the center of the square and announce songs by calling out their page numbers from the most recent revision of the 1844 book, which stays open on the laps of most. Before they launch into a song, the leader has the group "sing the notes" of the melody while naming the shapes: "fa, sol, la." Pitches are adjusted to meet the needs of the group, so songs may or may not be sung in the keys in which they are written.

The leaders keep time with their hands, turn to coax the best performance from each section, and sometimes scold unruly children at the edge of the group with a well-aimed look. Meanwhile, the singers beat time with their feet, sing as if their lives depended upon it, and often are so swept away by the experience that their faces are portraits of joy.

Near the center of the group, the music not only leaves your ears ringing but can be felt thumping in your chest and abdomen. Veteran harpers tell a tale, perhaps apocryphal, that someone once measured the sound inside the hollow square and came up with a reading of just over 100 decibels--which approaches the level of an average rock concert, at least from a few rows back.

But volume is only one characteristic of Sacred Harp.

Instead of the usual triads found in religious music, the chords are filled with octaves, fourths and fifths. There is also the occasional discordant note, which somehow contributes to the power and also manages to send chills down your spine.

"It's way cathartic," Gronau said.

Primal appeal

Named for an 1844 book that collected the popular ballads and church hymns of the day, the Sacred Harp-style is sometimes called "shape note" because of its primitive system of notation.

Although the tradtions began in New England, it quickly spread to the Midwest and antebellum South. Singing masters would travel from town to town, give lesson, and largely make their living by the sale of the oblong tune books such as "The Sacred Harp."

Although the tradtions began in New England, it quickly spread to the Midwest and antebellum South. Singing masters would travel from town to town, give lesson, and largely make their living by the sale of the oblong tune books such as "The Sacred Harp."

Their method taught musical sight reading by combining solmization, or syllable singing, with a notation system of four shapes that represent intervals instead of absolute pitches: triangle, oval, rectangle and diamond.

The advantage was that students unschooled in tradtitional musical notation could learn to sight-read quickly. Also, in the days long before television took the place of the family hearth or village well, the singing schools were an important social function.

"The singing master often appeared with a blackboard, charts showing tonal steps and their changes with keys, a pointer, pitchpipe, an armful of tune books, a love for music, and an earnest desire to teach people to sing," writes Shirley Bean, an associate professor of music at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, in the introduction to "The Missouri Harmony," a collection of 1820's frontier hymns reprinted recently by the University of Nebraska Press.

"The hopeful scholars brought firewood, slates or lapboards, candles, and an eagerness to learn the art of singing. The candles were sealed to the corners of the slates or boards to supply light. Seating was usually arranged in a semicircle severals rows deep. Instruction commenced with a presentation of the rudiments of music. . .soon the group was given exercises in voice placement."

Although most of the songs are religious in nature, some are ballads or commemorate events contemporary to the tune books. Some are unabashedly patriotic.

The spirits of Washington, Warren, Montgomery / lookdown from the clouds with bright aspect serene, begins a tune called "The American Star," which cites a trio of Revolutionary War heroes. Come, soldier, a tear and a toast to their memory / Rejoicing they'll see us as they once have been.

Other tunes can be described only as somber, even morbid.

Remember, you are hast'ning on / To death's dark, gloomy shade, the young are warned in "New Topia. " Your joys on earth will soon be gone / Your flesh in dust be laid.

"The words are imortant," observed Karen Isbell, a former president and founding member of the St. Louis singing group. "They're from a time when life was brutal. People had a different view of God and religion back then--primal, really stark and stripped down--and frankly, I think that's part of the appeal. Life mattered."

Rediscovery of style

While the music eventually died out in New England and the Midwest, it was passed uncorrupted from generation to generation in Primitive Baptist and other churches in the deep South. When a revival of interest in Sacred Harp music began around 1983 in places like Chicago and St. Louis, it was the Southern harpers who eventually showed the newcomers how to sing it full bore.

"We had been struggling along on our own," said Gronau, another founding member of the St. Louis Shape Note Singers.

At first, the members passed around barely legible photocopies from the original tune books, met in attics and basements, and tried their best to conjure the magic the printed matter only hinted at. Then, it occurred to Gronau to seek out those who had grown up in the tradtion, in much the same way blues fanatics had scoured the Mississippi delta seeking links to Robert Johnson and other masters. The result, Gronau said, was a rediscovery of a style that was "crisp and clean."

Also, Gronau learned, Sacred Harp is nothing short of a subculture based on a sort of musical communion, and bolstered by a tradition of shared meals and old-fashioned sensibilities. Harpers may travel across the state to attend a one-day "singing," or across the counry to attend one of the two-day state conventions like last weekend's 16 Annual Missouri Convention at Pinckney, for which the St. Louis group was host.

One of the new singers was Steven Henness, 28, a postgraduate student at the University of Missouri in Columbia. Henness, who holds a master's degree in rural sociology, had been traveling the state gathering information for a research project on community development when he heard of the upcoming convention. Although he attended because of his academic interest in rural tradtions, he soon found himself in the tenor section, singing from a copy of "The Sacred Harp."

"It was both exhausting and energizing at the same time," Henness said. "Instead of just trying to mechanically hit each note one after the other, I found myself being lost in the rhythm and power of the thing."

Also, Henness, the reason Sacred Harp is growing in popularity may be that it allows individuals "to ground their identities" in a tradition that is bigger and older than themselves. This, he said, is becoming increasingly difficult in a world that keeps changing faster than our forefathers could have imagined.

"I was not raised in this kind of tradition," said Elizabeth Senger, who drove with her family from LaCrosse, Wis., to attend the convention. "I was at a folk festival and I heard this stuff at a distance. I was curious, went to take a look, and somebody put a book in my hand."

For Senger, her faith is part of the experience.

"I find I worship better here than in my home church," she said. "There is a power to this kind of music that you don't find in popular culture. You feel connected to people that lived a hundred or more years ago. This morning, for example, we sang about the death of George Washington."

Another attraction, Senger said, is the democratic nature of the event: Song leaders are male and female, young and old, religious and not.

"You know, you hear people talk a lot about jazz as the only style of music that is native to America," she said. "Well there's this, too."

Popular gospel song has uncertain origin

Of all the songs in the Sacred harp tradition, the most popular is a simple tune called "Amazing Grace." Listed at the top of Page 45 of "The Sacred Harp," an 1844 collection of hymns, the song is titled "New Britain."

Many of the tunes in the collection are named for locations that have little to do with the lyrics, but which may reflect the titles of older melodies to which the words were grafted. The origin of the music for "Amazing Grace," however, is uncertain.

The words were written by John Newton, a former slave ship captain. By his mid-20's Newton was engaged in the horrific trade, in which slaves were packed into ships like cordwood and traded in the New World for sugar and molasses, which were taken back to England.

On May 10, 1748, Newton appealed to God to steer his ship safely through a violent storm. Just when it seemed the ship would sink, Newton uttered a simple request: "Lord, have mercy upon us." Although his prayer was answered, he continued in the slave trade for several more years, but gave it up because of ill health and eventually becme a minister in the Church of England.

At Olney, Newton became friends with the poet John Cowper, who helped him with his services. Together, they resolved to write a new hymn for each weekly service and prayer meeting. One of the hymns that resulted was "Amazing Grace," and it was first published in 1779.

Newton wrote several hundred other hymns and kept extensive journals, which have provided many modern historians with a glimpse of the 18th century slave trade. He died Dec. 21, 1807, in London, at the age of 84. Ironically, the "wretch" who once could see had gone blind.

The tune "New Britain" first appeared in a book published in 1829 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Since that time, more than 24 different tues have been published for "Amazing Grace," although many are variations of the one found in "The Sacred Harp."

The first stanza found in many contemporary hymnals, which begins "When we've been there ten thousand years," was not penned by Newton. It first appeared in 1909 and appears to be from an anonymous English folk hymn.

Newton's final stanza:

The earth shall soon dissolve like,

The sun forbear to shine;

But God, who call'd me here below,

Will be forever mine.

Photo captions, from top to bottom:

The hollow square as seen from the balcony of St. John's United Church of Christ in Pinckney, Mo. on March 10, 2001. This was the sixteenth annual Missouri State Scared Harp Singing Convention. From the left, basses, tenors, trebles and in front of the altar, altos.

Cassie Franklin, Henegar, Ala., leads the class in song 222-Ocean on Sunday, March 11, 2001 during the sixteenth annual Missouri State Sacred Harp Singing Convention in Pinckney, Mo. at the St. John's United Church of Christ. She sang both a solo unaccompanied song, Lady Margaret, and as a member of the Sacred Harp Singers for the soundtrack of the movie Cold Mountain released Dec. 25, 2003.

William Shetter, Bloomington, Ind., sings song 308-Parting Friends (Second) on Saturday, March 10, 2001 during the sixteenth annual Missouri State Sacred Harp Singing Convention at the St. John's United Church of Christ in Pinckney, Mo.

PINCKNEY, Mo.--A stone's throw north of the Missouri River, where Highway 94 crosses a one-lane bridge and wends its way across the rich bottom land toward Jefferson City, shines a white country church against the muted background of late winter.

PINCKNEY, Mo.--A stone's throw north of the Missouri River, where Highway 94 crosses a one-lane bridge and wends its way across the rich bottom land toward Jefferson City, shines a white country church against the muted background of late winter.Here, beneath the peaked roof of the 131-year-old St. John's United Church of Christ, time stood still for an eclectic group of singers who practice an archaic form of music known as Sacred Harp.

"It expresses your feelings about God, about how it feels deep down inside your heart,"explained 48-year-old Alice Moran, who was one of a handful of Joplin-area singers at the two-day convention.

Others, however, said religion isn't necessary.

Gary Gronau, a 57-year-old folk music fan and self-described '60's civil-rights activist from St. Louis, cited the music itself as the biggest draw.

"In this room there are a lot of people who are very strongly religious, and then there are people who are atheists--like me," he said.

Unlike most forms of music, which are intended for an audience, Sacred Harp is meant to be experienced. Harpers sing primarily for the joy of singing, said Gronau, and he repeated a quote attributed to legendary Georgia singer Hugh McGraw: "I will travel across the country to sing Sacred Harp, but I wouldn't walk across the street to listen to it."

Unlike most forms of music, which are intended for an audience, Sacred Harp is meant to be experienced. Harpers sing primarily for the joy of singing, said Gronau, and he repeated a quote attributed to legendary Georgia singer Hugh McGraw: "I will travel across the country to sing Sacred Harp, but I wouldn't walk across the street to listen to it."

Hollow square

For the uninitiated, the sound can be unpleasant. The lyrics are difficult to understand, unless a printed version is handy, and the seating arrangement of the singers is unlike that of any other kind of performance; unless you're participating, you're looking at their backs.

Members of the congregation sit in what is traditionally called a "hollow square," facing one another, and the music is divided into four parts, from bass to treble, with the melody carried by the tenors.

Song leaders stand in the center of the square and announce songs by calling out their page numbers from the most recent revision of the 1844 book, which stays open on the laps of most. Before they launch into a song, the leader has the group "sing the notes" of the melody while naming the shapes: "fa, sol, la." Pitches are adjusted to meet the needs of the group, so songs may or may not be sung in the keys in which they are written.

The leaders keep time with their hands, turn to coax the best performance from each section, and sometimes scold unruly children at the edge of the group with a well-aimed look. Meanwhile, the singers beat time with their feet, sing as if their lives depended upon it, and often are so swept away by the experience that their faces are portraits of joy.

Near the center of the group, the music not only leaves your ears ringing but can be felt thumping in your chest and abdomen. Veteran harpers tell a tale, perhaps apocryphal, that someone once measured the sound inside the hollow square and came up with a reading of just over 100 decibels--which approaches the level of an average rock concert, at least from a few rows back.

But volume is only one characteristic of Sacred Harp.

Instead of the usual triads found in religious music, the chords are filled with octaves, fourths and fifths. There is also the occasional discordant note, which somehow contributes to the power and also manages to send chills down your spine.

"It's way cathartic," Gronau said.

Primal appeal

Named for an 1844 book that collected the popular ballads and church hymns of the day, the Sacred Harp-style is sometimes called "shape note" because of its primitive system of notation.

Although the tradtions began in New England, it quickly spread to the Midwest and antebellum South. Singing masters would travel from town to town, give lesson, and largely make their living by the sale of the oblong tune books such as "The Sacred Harp."

Although the tradtions began in New England, it quickly spread to the Midwest and antebellum South. Singing masters would travel from town to town, give lesson, and largely make their living by the sale of the oblong tune books such as "The Sacred Harp."Their method taught musical sight reading by combining solmization, or syllable singing, with a notation system of four shapes that represent intervals instead of absolute pitches: triangle, oval, rectangle and diamond.

The advantage was that students unschooled in tradtitional musical notation could learn to sight-read quickly. Also, in the days long before television took the place of the family hearth or village well, the singing schools were an important social function.

"The singing master often appeared with a blackboard, charts showing tonal steps and their changes with keys, a pointer, pitchpipe, an armful of tune books, a love for music, and an earnest desire to teach people to sing," writes Shirley Bean, an associate professor of music at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, in the introduction to "The Missouri Harmony," a collection of 1820's frontier hymns reprinted recently by the University of Nebraska Press.

"The hopeful scholars brought firewood, slates or lapboards, candles, and an eagerness to learn the art of singing. The candles were sealed to the corners of the slates or boards to supply light. Seating was usually arranged in a semicircle severals rows deep. Instruction commenced with a presentation of the rudiments of music. . .soon the group was given exercises in voice placement."

Although most of the songs are religious in nature, some are ballads or commemorate events contemporary to the tune books. Some are unabashedly patriotic.

The spirits of Washington, Warren, Montgomery / lookdown from the clouds with bright aspect serene, begins a tune called "The American Star," which cites a trio of Revolutionary War heroes. Come, soldier, a tear and a toast to their memory / Rejoicing they'll see us as they once have been.

Other tunes can be described only as somber, even morbid.

Remember, you are hast'ning on / To death's dark, gloomy shade, the young are warned in "New Topia. " Your joys on earth will soon be gone / Your flesh in dust be laid.

"The words are imortant," observed Karen Isbell, a former president and founding member of the St. Louis singing group. "They're from a time when life was brutal. People had a different view of God and religion back then--primal, really stark and stripped down--and frankly, I think that's part of the appeal. Life mattered."

Rediscovery of style

While the music eventually died out in New England and the Midwest, it was passed uncorrupted from generation to generation in Primitive Baptist and other churches in the deep South. When a revival of interest in Sacred Harp music began around 1983 in places like Chicago and St. Louis, it was the Southern harpers who eventually showed the newcomers how to sing it full bore.

"We had been struggling along on our own," said Gronau, another founding member of the St. Louis Shape Note Singers.

At first, the members passed around barely legible photocopies from the original tune books, met in attics and basements, and tried their best to conjure the magic the printed matter only hinted at. Then, it occurred to Gronau to seek out those who had grown up in the tradtion, in much the same way blues fanatics had scoured the Mississippi delta seeking links to Robert Johnson and other masters. The result, Gronau said, was a rediscovery of a style that was "crisp and clean."

Also, Gronau learned, Sacred Harp is nothing short of a subculture based on a sort of musical communion, and bolstered by a tradition of shared meals and old-fashioned sensibilities. Harpers may travel across the state to attend a one-day "singing," or across the counry to attend one of the two-day state conventions like last weekend's 16 Annual Missouri Convention at Pinckney, for which the St. Louis group was host.

One of the new singers was Steven Henness, 28, a postgraduate student at the University of Missouri in Columbia. Henness, who holds a master's degree in rural sociology, had been traveling the state gathering information for a research project on community development when he heard of the upcoming convention. Although he attended because of his academic interest in rural tradtions, he soon found himself in the tenor section, singing from a copy of "The Sacred Harp."

"It was both exhausting and energizing at the same time," Henness said. "Instead of just trying to mechanically hit each note one after the other, I found myself being lost in the rhythm and power of the thing."

Also, Henness, the reason Sacred Harp is growing in popularity may be that it allows individuals "to ground their identities" in a tradition that is bigger and older than themselves. This, he said, is becoming increasingly difficult in a world that keeps changing faster than our forefathers could have imagined.

"I was not raised in this kind of tradition," said Elizabeth Senger, who drove with her family from LaCrosse, Wis., to attend the convention. "I was at a folk festival and I heard this stuff at a distance. I was curious, went to take a look, and somebody put a book in my hand."

For Senger, her faith is part of the experience.

"I find I worship better here than in my home church," she said. "There is a power to this kind of music that you don't find in popular culture. You feel connected to people that lived a hundred or more years ago. This morning, for example, we sang about the death of George Washington."

Another attraction, Senger said, is the democratic nature of the event: Song leaders are male and female, young and old, religious and not.

"You know, you hear people talk a lot about jazz as the only style of music that is native to America," she said. "Well there's this, too."

Popular gospel song has uncertain origin

Of all the songs in the Sacred harp tradition, the most popular is a simple tune called "Amazing Grace." Listed at the top of Page 45 of "The Sacred Harp," an 1844 collection of hymns, the song is titled "New Britain."

Many of the tunes in the collection are named for locations that have little to do with the lyrics, but which may reflect the titles of older melodies to which the words were grafted. The origin of the music for "Amazing Grace," however, is uncertain.

The words were written by John Newton, a former slave ship captain. By his mid-20's Newton was engaged in the horrific trade, in which slaves were packed into ships like cordwood and traded in the New World for sugar and molasses, which were taken back to England.

On May 10, 1748, Newton appealed to God to steer his ship safely through a violent storm. Just when it seemed the ship would sink, Newton uttered a simple request: "Lord, have mercy upon us." Although his prayer was answered, he continued in the slave trade for several more years, but gave it up because of ill health and eventually becme a minister in the Church of England.

At Olney, Newton became friends with the poet John Cowper, who helped him with his services. Together, they resolved to write a new hymn for each weekly service and prayer meeting. One of the hymns that resulted was "Amazing Grace," and it was first published in 1779.

Newton wrote several hundred other hymns and kept extensive journals, which have provided many modern historians with a glimpse of the 18th century slave trade. He died Dec. 21, 1807, in London, at the age of 84. Ironically, the "wretch" who once could see had gone blind.

The tune "New Britain" first appeared in a book published in 1829 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Since that time, more than 24 different tues have been published for "Amazing Grace," although many are variations of the one found in "The Sacred Harp."

The first stanza found in many contemporary hymnals, which begins "When we've been there ten thousand years," was not penned by Newton. It first appeared in 1909 and appears to be from an anonymous English folk hymn.

Newton's final stanza:

The earth shall soon dissolve like,

The sun forbear to shine;

But God, who call'd me here below,

Will be forever mine.

Photo captions, from top to bottom:

The hollow square as seen from the balcony of St. John's United Church of Christ in Pinckney, Mo. on March 10, 2001. This was the sixteenth annual Missouri State Scared Harp Singing Convention. From the left, basses, tenors, trebles and in front of the altar, altos.

Cassie Franklin, Henegar, Ala., leads the class in song 222-Ocean on Sunday, March 11, 2001 during the sixteenth annual Missouri State Sacred Harp Singing Convention in Pinckney, Mo. at the St. John's United Church of Christ. She sang both a solo unaccompanied song, Lady Margaret, and as a member of the Sacred Harp Singers for the soundtrack of the movie Cold Mountain released Dec. 25, 2003.

William Shetter, Bloomington, Ind., sings song 308-Parting Friends (Second) on Saturday, March 10, 2001 during the sixteenth annual Missouri State Sacred Harp Singing Convention at the St. John's United Church of Christ in Pinckney, Mo.

Sunday, September 16, 2007

Lowell Davis

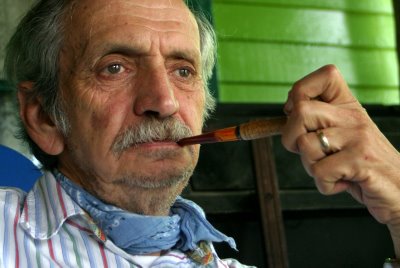

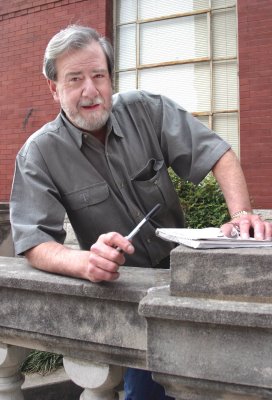

Okay, enough death and destruction photos. Let's change the tone a bit -- here's my friend Lowell Davis, sitting on the porch of his cabin near Carthage and looking reflective. Lowell is an internationally-known artist and the subject of a documentary I've been shooting for a few years now. I took this photo July 27, 2005. What's amazing about Lowell is that he's recreated around him the town of his boyhood. No kidding. He grew up at Red Oak, in Lawrence County, Missouri, and he loved it so much that he has built his own version (called Red Oak II) east of Carthage. There's a feed store, a church, a gas station, a fire department, a Civil War-era cabin or two, and much more. It's not an exact duplicate, but is rather "reimagined" with Lowell's pronounced sense of whimsy. Below are examples.

Okay, enough death and destruction photos. Let's change the tone a bit -- here's my friend Lowell Davis, sitting on the porch of his cabin near Carthage and looking reflective. Lowell is an internationally-known artist and the subject of a documentary I've been shooting for a few years now. I took this photo July 27, 2005. What's amazing about Lowell is that he's recreated around him the town of his boyhood. No kidding. He grew up at Red Oak, in Lawrence County, Missouri, and he loved it so much that he has built his own version (called Red Oak II) east of Carthage. There's a feed store, a church, a gas station, a fire department, a Civil War-era cabin or two, and much more. It's not an exact duplicate, but is rather "reimagined" with Lowell's pronounced sense of whimsy. Below are examples.

Red Oak II Fire Truck and Church

Red Oak II Gas Station

Red Oak II MIL House

Monday, August 27, 2007

So long, J.D. Cash

Earlier this year, I was asked by Mother Jones magazine for permission to use a photo of investigative reporter J.D. Cash that I had taken back in 2004 at the state trial for Oklahoma City bomber Terry Nichols. Never heard back from the magazine after transmitting the photos, but found online that they story had run in last month's edition of the magazine.

Earlier this year, I was asked by Mother Jones magazine for permission to use a photo of investigative reporter J.D. Cash that I had taken back in 2004 at the state trial for Oklahoma City bomber Terry Nichols. Never heard back from the magazine after transmitting the photos, but found online that they story had run in last month's edition of the magazine.I read the story and was shocked to learn that Cash had died in May. Fuck. This is not the kind of entry I envisioned when I began this blog.

The photo abovet was taken March 22, 2004, outside the courthouse at McAlester. I covered the trial for the British magazine, Fortean Times, in a story called "White Noise."Cash -- who wrote investigative stories for the tiny McCurtain Gazette -- was featured in the article. He had gained notoriety by questioning whether Nichols and Timothy McVeigh had acted alone, or whether a group called the Aryan Republican Army was also involved. I had also done some original reporting on the ARA, and they kept a safehouse at my longtime hometown of Pittsburg, Kansas.

The Pittsburg safehouse is at left, in a photo I took in February 2004. The ARA robbed at least 22 banks across the Midwest and were the poster children for white supremacist nutjobs - they were attempting to finance an all-out race war. The gang was led by boyhood friends Pete Langan and Richard Guthrie. Timothy McVeigh, who was executed for the OKC bombing, may have beena wheel man for the gang. When Langan was outed as a cross-dressing transexual, the gang fell apart. Guthrie and Langan were caught by the feds in 1996; Guthrie committed suicide in prison and Langan is now serving his time at the Supermax prison at Florence, Colorado.

Cash dieda couple of days after the Greensburg tornado, so I was otherwise occupied. But I still feel badly that he died and I didn't know about his passing. He was a terrific guy, and in addition to writing for the Gazette, he also did a local program, and he had me on as a guest a time or two promoting some book or another. Probably The Moon Pool.

Here's what the Associated Press ran on his death:

Published: May 07, 2007 4:55 PM ET

TULSA, Okla. (AP) Newspaper reporter J.D. Cash of the McCurtain Daily Gazette has died at age 55. Cash died at a Tulsa hospital Sunday following after suffering from liver disease and pneumonia.

Cash had spent the past 12 years reporting on the Oklahoma City bombing, including a report from a woman who said she was an undercover agent who warned the government of plans to bomb federal buildings in 1995.

He's survived by his mother.

A private funeral service is planned in Tulsa.

Cash did not have a journalistic background. He came to reporting for one story, and one story only: the Oklahoma City bombing. He did it better than anybody else, he did it for a newspaper with a circulation so small that most journalists cited it with a chuckle, and he came closer to the truth than anybody else. Damn.

And come to think of it, Mother Jones never paid me for the photo. But maybe they didn't use it. Also, J.D. never told me he was sick. But then, as tough as he was, he wouldn't. But I'm glad to have known him, and glad to have taken a photo that tells his story -- outside a courthouse, notebook and pen in hand.

Wednesday, August 22, 2007

Greensburg Neighbor

www.neighbor-to-neighbor.net

Big Well Sign

Big Well -- August 2007

Monday, August 20, 2007

More Katrina 2005

Top photo: The French Quarter, as seen fhrough the turret of a Humvee. I rode from West Plains, Missouri, to New Orleans in one, and I can tell you that they are very loud and the seat cushions don't have much padding. Bottom photo: A boy waves at a Missouri National Guardsman at a food distribtuion site at Kenner, La.

Katrina 2005

It's coming up on the second anniversary of Katrina. I took these photos while embedded with the 1138 Military Police, a Missouri National Guard unit from West Plains

The top photo is ruins of a building in the French Quarter; the middle shot is a street scene a few days after the hurricans; and the bottom is a copy handing out MREs and bottled water to Bourbon Street residents who refused to evacuate.

The top photo is ruins of a building in the French Quarter; the middle shot is a street scene a few days after the hurricans; and the bottom is a copy handing out MREs and bottled water to Bourbon Street residents who refused to evacuate.

Monday, August 6, 2007

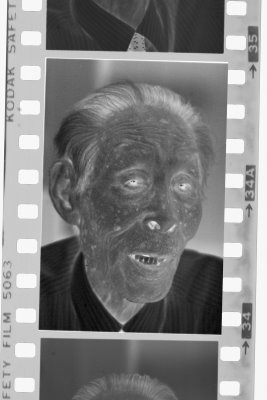

Hiroshima 1986 - Frame 35A

Another Hiroshima anniversary photo. Here, the old man (see post below) describes the fireball and mushroom cloud he saw on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945. His 14-year-old son, Kenji, died in the conflagration. The man was one the oldest living hibakusha, which means those who received the bomb. He had never before spoken about the events of that morning, and was particularly suspicious of an American reporter. When he asked, through an interpreter, why he should talk to me, I pulled out my billfold and showed him photographs of my children -- Julie, who was 10, and Abby, who was a baby. My third daughter, Megan, would not be born for another four years.

Another Hiroshima anniversary photo. Here, the old man (see post below) describes the fireball and mushroom cloud he saw on the morning of Aug. 6, 1945. His 14-year-old son, Kenji, died in the conflagration. The man was one the oldest living hibakusha, which means those who received the bomb. He had never before spoken about the events of that morning, and was particularly suspicious of an American reporter. When he asked, through an interpreter, why he should talk to me, I pulled out my billfold and showed him photographs of my children -- Julie, who was 10, and Abby, who was a baby. My third daughter, Megan, would not be born for another four years.

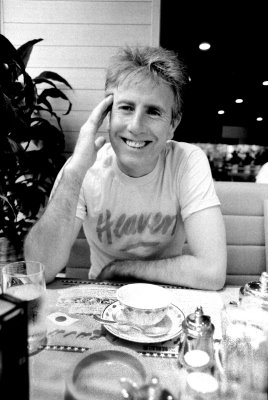

The Past is Just a Good Bye

Today is the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. In 1986, I was in Japan interviewing survivors of the bombing for a series of photos and articles. I also interviewed was Graham Nash, who bought me a piece of pecan pie. Despite the rock star lifestyle -- he breezed into the hotel with an entourage in tow, including a gorgeous woman he had taken shopping -- he was a nice chap. He was 44 at the time, and I was 26.

Today is the anniversary of the bombing of Hiroshima. In 1986, I was in Japan interviewing survivors of the bombing for a series of photos and articles. I also interviewed was Graham Nash, who bought me a piece of pecan pie. Despite the rock star lifestyle -- he breezed into the hotel with an entourage in tow, including a gorgeous woman he had taken shopping -- he was a nice chap. He was 44 at the time, and I was 26.He explained that he had formed his anti-nuclear views during a stay-aboard visit to the Calypso, where Jacques Cousteau had explained to him that the waste product of the nuclear power generation cycle is weapons-grade plutonium. All nuclear power plants produce plutonium, and originally the government was going to buy back all of this stuff to make bombs with. But that plan was scrapped for fear of plutonium proliferation, and in the early 1980s the plants were ordered to keep all this stuff in cooling ponds on site until a secure storage facility could be built. Now, it's 2007 and that storage facility -- now being built a Yucca Mountain, Arizona -- still has not come on line. The night of the interview, I heard Graham sing "Teach You Children" at a peace rally.

Wednesday, August 1, 2007

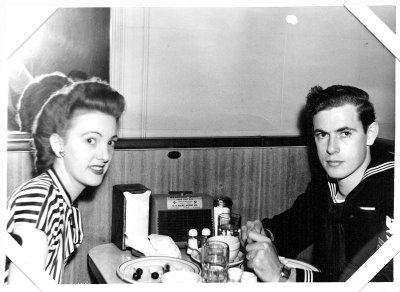

Seattle 1945 - Frame 7A

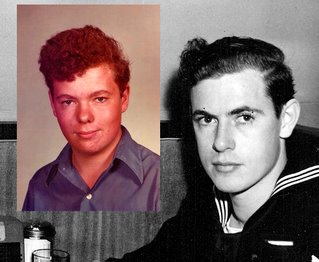

Another souvenir photo, this one taken at Hollingswoth's Melody Lane, Seattle. My father was 20, and less than a year before had been on the USS Pennsylvania at Leyte Gulf -- the largest naval battle in modern history. I wish the photograph were as in focus as the one below, because the composition is much better. Information on the back identifies the photo as 7A, taken Dec. 11, 1945, and that additional copies are available for $1.35.

Another souvenir photo, this one taken at Hollingswoth's Melody Lane, Seattle. My father was 20, and less than a year before had been on the USS Pennsylvania at Leyte Gulf -- the largest naval battle in modern history. I wish the photograph were as in focus as the one below, because the composition is much better. Information on the back identifies the photo as 7A, taken Dec. 11, 1945, and that additional copies are available for $1.35.My parents separated in 1975 but never divorced. My mother died of cancer in 1986, a few months after I returned from Japan. She was 59. My father died in 1997, age 73. He had remarried. These photos were found in a Christmas tin recently while cleaning out my (former) garage in the wake of my divorce. I read somewhere that photographs last longer than most intentions.

Thirty Years Later

San Francisco 1945

Here's a souvenir photograph of my parents at the Gold Coast, 972 Market Street, San Francisco, taken June 1, 1945. My father, Carl McCoy, is a yeoman on the battleship USS Pennsylvania. My mother, Mary Carter McCoy, is 18 years old. It was two months before the atomic bomb was dropped. When I went to Hiroshima in 1986, my mother wrote the emperor urging him not to allow me in the country -- I was, she said, a traitor because my father had sailed against the Japanese.

Here's a souvenir photograph of my parents at the Gold Coast, 972 Market Street, San Francisco, taken June 1, 1945. My father, Carl McCoy, is a yeoman on the battleship USS Pennsylvania. My mother, Mary Carter McCoy, is 18 years old. It was two months before the atomic bomb was dropped. When I went to Hiroshima in 1986, my mother wrote the emperor urging him not to allow me in the country -- I was, she said, a traitor because my father had sailed against the Japanese.

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

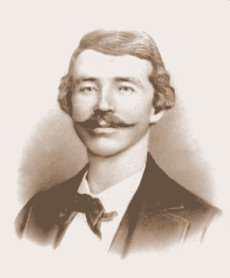

Quantrill's Birthday

William Clarke Quantrill was born 170 years ago today at Canal Dover, Ohio.

William Clarke Quantrill was born 170 years ago today at Canal Dover, Ohio.He was only 27 when he died, after being shot in the back by Edwin Terrell's band of guerrilla hunters, but he was already notorious for burning the abolitionist stronghold of Lawrence, Kansas, and killing a couple of hundred men and boys in 1863.

At about 4:20 yesterday morning, I completed revisions to I, Quantrill. The novel will be published in 2008 by Penguin. It is with relief that I bid Captain Quantrill farewell -- frankly, I'm sick of living in his head. He's a fascinating character, but disturbing, and I'm glad to be free of him, at least until I have to proof the galleys.

So, for all of you Leos who share Quantrill's birthday -- remain calm and think happy thoughts.

Saturday, July 28, 2007

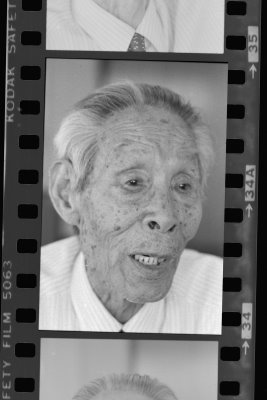

Hiroshima 1986 - Frame 34A

The anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima is coming up -- Friday, Aug. 6 -- and this got me to thinking about the hundreds of photographs I took there on assignment in 1986. For nearly six weeks, I interviewed through interpeters scores of atomic bomb survivors, such as the old man at left -- who described how he had sent his 14-year-old son, Kenji, to work in the munitions factory that morning and never saw him again.

The anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima is coming up -- Friday, Aug. 6 -- and this got me to thinking about the hundreds of photographs I took there on assignment in 1986. For nearly six weeks, I interviewed through interpeters scores of atomic bomb survivors, such as the old man at left -- who described how he had sent his 14-year-old son, Kenji, to work in the munitions factory that morning and never saw him again.The survivors are called hibakusha, literally "those who received the bomb," and for decades were discriminated against by fellow Japanese as somehow unclean, unfit to employ or to marry. This topic stirs up a number of issues -- the Cold War (remember that?), rolling my own film from bulk rolls, developing it in aluminum tanks on stainless steel reels, dodging and burning the photographs in the enlarger -- and the disconcerting fact that 21 years have passed since this photograph was taken.

That's a generation.

That is a bit profound, so you're likely to get more musings -- and perhaps more images -- on then and now as the anniversaries of Hiroshima and Nagasaki approach.

Technical Note:

For the purists, and I know you're out there, I will cop to some sloppy Photoshopping of the above image (Well, I didn't have all night, did I?) to make the original negative strip and frame appear as a positive, as in a contact sheet. The original negative would resemble the one at left, or something close to it, as seen on a light table. The photo was taken on Kodak TRI-X with a Canon F1-n and, if I remember correctly, a 135mm 2.8 lens. Available light, of course. One of the things that bothers me about the current state of photojournalism is that nearly every photograph, even in bright sunlight, is taken with a strobe to fill shadows, especially in faces. That's because digital has a much narrower exposure latitude than film. But strobe still seems like cheating to me. Even though I shoot striclty digital now -- most photos on this blog are taken with a Canon EOS 10D -- I still rely on available light. I know, I'm a dinosaur.

For the purists, and I know you're out there, I will cop to some sloppy Photoshopping of the above image (Well, I didn't have all night, did I?) to make the original negative strip and frame appear as a positive, as in a contact sheet. The original negative would resemble the one at left, or something close to it, as seen on a light table. The photo was taken on Kodak TRI-X with a Canon F1-n and, if I remember correctly, a 135mm 2.8 lens. Available light, of course. One of the things that bothers me about the current state of photojournalism is that nearly every photograph, even in bright sunlight, is taken with a strobe to fill shadows, especially in faces. That's because digital has a much narrower exposure latitude than film. But strobe still seems like cheating to me. Even though I shoot striclty digital now -- most photos on this blog are taken with a Canon EOS 10D -- I still rely on available light. I know, I'm a dinosaur.

Friday, July 27, 2007

Another Reason to Love Michael Chabon

I don't have a problem with many uses of the word genre, just certain ones. I have the most trouble when these labels are used to prevent discussion, to prevent a work from being taken seriously as literature. When we say "genre," we generally mean "something crappy," something that would be sold in an airport. I hate to see great works of literature ghettoized, whereas others that conform to the rules, conventions, and procedures of the genre we call literary fiction get accorded greater esteem and privilege. I also have a problem with how books are marketed, with certain cover designs and typefaces. They're often stamped with an identity that has nothing to do with their effect on the reader. I subscribe to Sturgeon's Law, which is that "90 percent of everything is crud." I'm trying to say that they're all inherently equal—it's not what you do, it's the way you do it. The percentage of excellence isn't any higher in what's called literary fiction. -- Michael Chabon, interviewed by Elizabeth Benefiel at AV Club.

Thursday, July 26, 2007

Warehouse, Nelson County

Torula

Just one of the things which fascinated me during my research trip to Nelson County was the black stuff which clung to warehouses and fences and trees around the distilleries. It's called torula, and it is a yeast-like fungi that thrives on the fumes produced by the fermentation process. A lot of barns and fences far from any distilleries in the county are also painted black (where, in my neck of the woods in Kansas and Missouri, they would normally be white). It must be a cultural thing, a kind of nod to the county's heritage. This is just the kind of thing you find during a research trip but which might escape you during book research -- in fact, I found no reference to torula or this passion for black barns and fences in the WPA Guide to Kentucky or any of the other reference books I consulted.

Just one of the things which fascinated me during my research trip to Nelson County was the black stuff which clung to warehouses and fences and trees around the distilleries. It's called torula, and it is a yeast-like fungi that thrives on the fumes produced by the fermentation process. A lot of barns and fences far from any distilleries in the county are also painted black (where, in my neck of the woods in Kansas and Missouri, they would normally be white). It must be a cultural thing, a kind of nod to the county's heritage. This is just the kind of thing you find during a research trip but which might escape you during book research -- in fact, I found no reference to torula or this passion for black barns and fences in the WPA Guide to Kentucky or any of the other reference books I consulted.

St. John's Cemetery, Louisville

Wakefield, Kentucky

Wednesday, July 25, 2007

Prairie Spirit Trail - July '07

Catholic Cemetery, Louisville

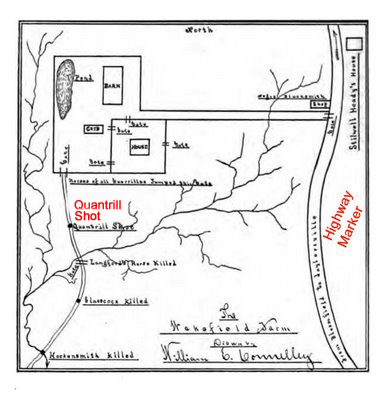

Wakefield Farm Map

Wakefield Farm Map

Here's the map of Wakefield Farm reproduced in William E. Connelley's Quantrill and the Border Wars (1910). I have added in red the spot where Quantrill was shot and the position, based on my reckoning, of the location of the historical marker, which appears in the photograph below. The GPS coordinates of the marker, for the geeks among us, are 37.97241 / - 85.31041.

Here's the map of Wakefield Farm reproduced in William E. Connelley's Quantrill and the Border Wars (1910). I have added in red the spot where Quantrill was shot and the position, based on my reckoning, of the location of the historical marker, which appears in the photograph below. The GPS coordinates of the marker, for the geeks among us, are 37.97241 / - 85.31041.Wakefield Farm

Monday, July 9, 2007

Haviland Festival - 7 July '07

Haviland Festival - 7 July '07

Haviland Festival - 7 July '07

Friday, June 22, 2007

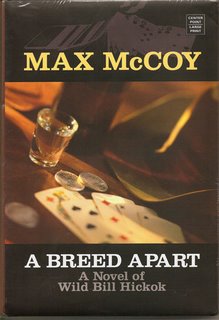

A Breed Apart Hardcover

Got home to find the hardbound large print edition of A Breed Apart waiting on me. I didn't even know those rights had been sold. My editor at Penguin, Brent Howard, FedExed a couple of courtesy copies of the book to me. He's a terrific guy and I'm not saying that just because he's my editor and I'm late with my next book. Brent and Signet did a great job with the paperback cover of the book -- it really pops -- and I like this cover of this edition as well, which is published by Center Point. I don't know who designed this cover, but I think it's a classic, and I just wanted to say thanks. So, great work! Now, A Breed Apart wasn't the original title, but that's another story...

Got home to find the hardbound large print edition of A Breed Apart waiting on me. I didn't even know those rights had been sold. My editor at Penguin, Brent Howard, FedExed a couple of courtesy copies of the book to me. He's a terrific guy and I'm not saying that just because he's my editor and I'm late with my next book. Brent and Signet did a great job with the paperback cover of the book -- it really pops -- and I like this cover of this edition as well, which is published by Center Point. I don't know who designed this cover, but I think it's a classic, and I just wanted to say thanks. So, great work! Now, A Breed Apart wasn't the original title, but that's another story...

Greensburg School - May '07

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)